Real ale is the quintessential British beer tradition – alive in the cask, naturally conditioned, and poured without added gas. Whether you run a village pub, volunteer at a beer festival, or just love a proper pint, understanding how real ale is brewed and served will help you appreciate why it tastes the way it does – and how to keep it at its best.

What makes “real ale” real?

At its heart, real ale is cask-conditioned beer. After primary fermentation at the brewery, the beer is racked into a cask with a touch of fermentable sugar and living yeast. That yeast continues to work inside the cask, producing gentle carbonation and developing flavour complexity. There’s no force-carbonation and no gas pressure pushing the beer to the glass – just gravity or a hand pump, which preserves the delicate mouthfeel and soft, natural sparkle.

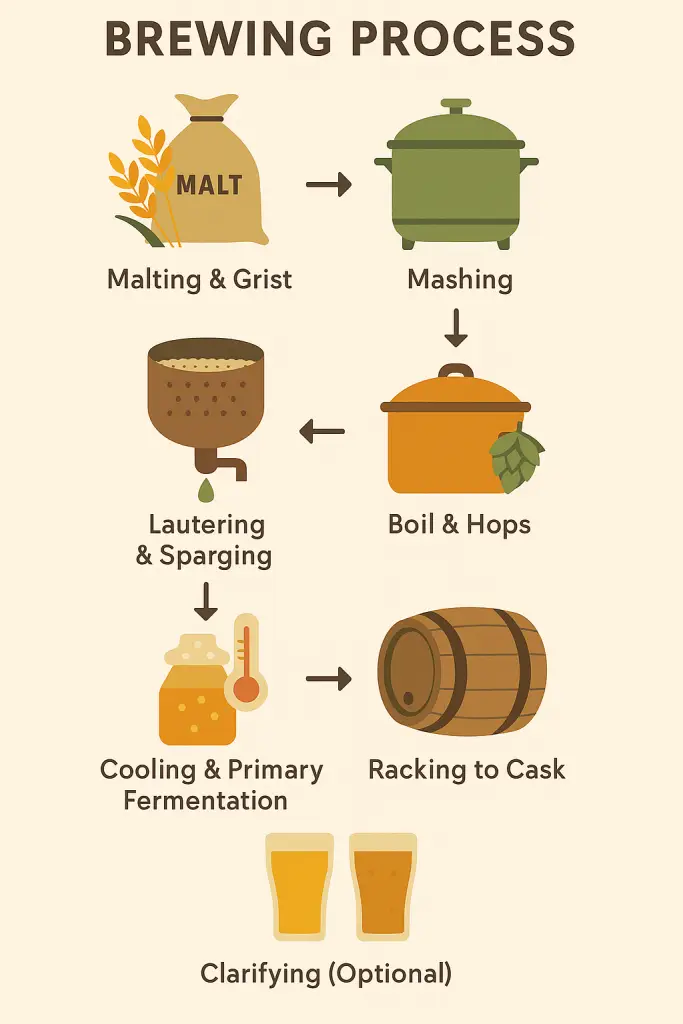

Brewing: step-by-step from malt to beer

1) Malting & grist

Real ale begins with malted barley (often with wheat or other cereals for body and head retention). Malting awakens natural enzymes in the grain; kilning fixes colour and flavour – ranging from pale cracker and biscuit notes to caramel and roast.

2) Mashing

The crushed malt (the grist) is mixed with hot water in a mash tun – typically in the 63–68 °C range – to convert starches into fermentable sugars. The goal is to create a sweet liquid called wort with the balance of fermentable and unfermentable sugars that gives real ale its rounded body.

3) Lautering & sparging

The wort is separated from the grain bed and rinsed (sparged) to capture more sugars, taking care not to extract tannins that can cause harshness.

4) Boil & hop additions

Wort is boiled for 60–90 minutes:

- Bittering hops early in the boil provide bitterness.

- Flavour and aroma hops late in the boil or at whirlpool add citrus, floral, spicy, or resinous notes.

Traditional English varieties (Fuggles, Goldings) lend earthy, herbal tones; modern UK or US varieties bring fruit-forward character.

5) Cooling & primary fermentation

Cooled wort is oxygenated and pitched with ale yeast (top-fermenting strains), typically fermenting around 18–22 °C. Most primary fermentations finish within a week, leaving a young beer that’s still evolving.

6) Racking to cask (the “real” bit)

Instead of force-carbonating into a keg, the brewer racks the beer into a cask (commonly a 9-gallon firkin). A measured amount of priming sugar and living yeast is present. The cask is sealed and conditioning continues – this secondary fermentation creates gentle, natural carbonation and polishes flavours.

7) Clarifying (or not)

Many traditional cask beers use finings (often isinglass) to help yeast flocculate, yielding a bright pint. Others are intentionally unfined – suitable for vegetarians/vegans and often hazier – trading clarity for texture and aroma. Either approach can be excellent when handled well.

Serving: handpulls, gravity, and good habits

1) Gravity dispense

The cask is stillaged on the back bar or in the cellar with a line through a simple tap. It’s as direct as it gets – minimal agitation, soft mouthfeel. Best for festivals or pubs with short runs.

2) Beer engine (handpull)

A cylinder-and-piston pump draws beer from the cellar to the bar. This adds a pleasant, gentle agitation that “wakes up” aromas and forms a tight head if a swan-neck and sparkler are used (regional preferences vary!).

Pouring a perfect pint

- Vent and condition the beer properly first; serving can’t fix a rushed cellar.

- Pull steadily; don’t saw at the handle. If using a sparkler, choose the right aperture to balance foam and body.

- Avoid unnecessary oxygen pickup – cap the cask when not serving (hard spile in) and minimise splashing in jugs or pitchers.

- Rotate stock: sell through within 3–5 days of tapping for peak freshness.

Why real ale tastes different from keg and bottle

- Natural conditioning in cask retains a soft, fine carbonation – more caress than prickle.

- Live yeast continues to evolve flavours after racking, adding depth and freshness.

- No extraneous gas means the malt, hops, and fermentation character aren’t scrubbed or carbonic-bitten.

- Cellarmanship brings a human touch – curation rather than mere storageso the same beer can sing or stumble depending on how it’s kept.

How does the Mitre pub give you the perfect pint?

We use the CaskWidge system, which we recommend. It helps to lengthen the life of the ale and draws the ale from the clearest part of the cask, the top, due to the float mechanism.